I just sent an essay on bell hooks’ Teaching to Transgress off to my lovely editors at Chronicle Vitae. This essay was one I had to wrangle because there were so many things that I wanted to say alongside all the things I needed to say. Or maybe, this essay wrangled me because it refused to let me go until I had it in the necessary form for publication. Plus, there was the added pressure that I was writing about the work of bell hooks, who I admire and adore, on teaching, of which I have serious and complicated feelings. hooks is a force to be reckoned with; reckoning takes time. Her writing makes me pause and think about how the world works (and how writing works). There was much, much wrangling. I spent much time.

What I’ve learned as an essayist is that I cannot predict how long an essay will take me to conjure, to think about, and then write. Some essays surprise me by how quick they seem, and others are long, drawn-out affairs, which take months (or occasionally years) to complete. Some essays require my complete attention for days and weeks. Others linger in the back of my mind until I’m ready to write them. They bounce around as I work on other topics. They catch me unaware as I rock my toddler to sleep. They appear when I wake up in the morning or as I pour a cup of coffee. Some linger waiting for me to commit. Other ideas dissipate leaving me with a faint impression that I should write about something. Ideas don’t always become essays, yet the ideas that refuse to go away often do.

The labor of making an essay is solitary and not-quite-visible. I started snapping photos of my process in part to make my efforts visible. Inspired by Austin Kleon’s Show Your Work, I thought it might be cool to show folks a glimpse of what I was writing, editing, or researching for my essays. For me, to show, and for you, to see. For this essay in particular, I’ve been trying to capture each stage. I created photographic evidence, if you will, of what I do, but not all work is visible. I can only document that which materializes. Please keep this in mind.

To start the essay on Teaching to Transgress, I had to read the book. I started and stopped reading it a few times because of other assignments and my children. (There’s usually a pile of books/research/Creative Nonfiction issues resting on my ottoman. I’m at varying stages in multiple projects at all times.)

I finally squared away time to read Teaching to Transgress. I underlined passages, wrote in the margins, and dog-eared the pages. Last year, I learned from my daughter’s librarian that these practices make me a terrible book friend. Yet, I’m not losing sleep over this. Weird. I tend to use different color pens when I reread to get a better sense of what caught my attention at first and later. I end up with conversations between former selves in the margins. (A quick note: I always misspell “bell” because my cat is Belle. My brain cannot bear the difference.)

I also like to tweet and Instagram what I’m reading. Usually with an “Amen. Go read this.”

Reading and rereading takes me hours. For this particular book, I didn’t keep track of how many, but it was more than five hours but less than eight. Reading the book, of course, is only the beginning of a review essay for me. I have to think about what I’ve learned and whether I have anything to say that is 1) coherent, 2) worth reading, and 3) intelligent. I don’t write just to write. I hope to add to conversations, write essays that have something to say, and get paid.

To suss out what I might write, I have conversations with Chris (aka Dr. Geese). He bears being my sounding board with good grace, wit, and excellent insights. Also, he refuses to let me take myself too seriously. This is more necessary that I care to admit out loud. Sometimes, I end up lecturing him, and he snaps a picture for all of the internet to see.

After I talk about what I plan to write, I brainstorm and journal. I make notes. (I wear awesome pink pants.)

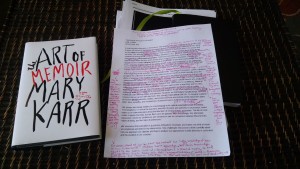

And then, I type. Much of what happens in the process of creation is internal. That’s the pretty way of saying all of this happens in my head. I imagine a beginning. (Figuring out how to begin is still the hardest part of writing for me). I decide against it. I imagine another. This goes on for a fair amount of time. Once I’ve found the beginning, I type. I fight with myself about word choice, sentence structure, and the length and position of paragraphs. I stall. I keep trying to type. When I lack the words or the necessary thought, I print out what I’ve written, and then, I edit in longhand. I have a seat on my comfy office love seat, grab pen, and edit on paper. This is my tried and true way to work through whatever is not working when I compose at the computer.

The edits and rewrites were pretty substantial. (But, Mary Karr is urging for me to finish, so I can read about the craft of memoir.) Once I don’t hate what I’ve revised, I stand up and return to my standing desk to input edits. I move back and forth through out the day as if movement is a symbol for progress. This essay was harder than I imagined it would be, so I ended up editing and revising by hand multiple times. I cleaved paragraphs for the sake of a better read. I dropped part of the narrative. I refocused on the main arc. I deleted a whole section about coming terms with no longer being a teacher.

The edits and rewrites were pretty substantial. (But, Mary Karr is urging for me to finish, so I can read about the craft of memoir.) Once I don’t hate what I’ve revised, I stand up and return to my standing desk to input edits. I move back and forth through out the day as if movement is a symbol for progress. This essay was harder than I imagined it would be, so I ended up editing and revising by hand multiple times. I cleaved paragraphs for the sake of a better read. I dropped part of the narrative. I refocused on the main arc. I deleted a whole section about coming terms with no longer being a teacher.

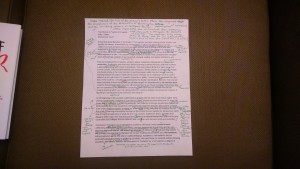

When an essay proves difficult, I often have to walk away for a short period of time. I took the weekend off from writing, which gave me needed time and space to figure out exactly what wasn’t working. Here’s the last round of on the page revisions.

There is a whole lot of green, but I realized what I needed to emphasize about hooks’ work. I wrote those lines at the top of the page as a guide post to what I should do. I revised with those lines in mind. When I returned to my computer, I continued to fight with sentences and structure. Sigh. I rearranged the essay for a better flow. Reworked the ending entirely, but finally achieved a polished essay for my editor. The essay doesn’t have to be perfect, but it should be clean, organized, and well-thought. She’ll do a round of edits. Another editor will too. They’ll send it back to me with revisions and queries. I’ll address their concerns and make sure I like how the piece reads. There are usually minor questions and queries for clarity and ease of reading. Since Vitae is a regular gig for me, I have a keen sense of my writing voice for those essays, which makes it easier to figure out my take for my columns. With my other essays, voice can be the most pressing question.

There’s usually a month or a few weeks between submission and revisions. By the time I receive the edits, I’m not mortally offended by my tone or what I managed to say. During the process of revising, I’m convinced that I’m an idiot who makes bad career decisions and can barely write emails much less essays. When I read with distance, I tend to be kinder to myself. I can also appreciate what the essay manages to do. With my approval and my excellent editors, the essay gets published and hopefully read by you.

When this essay is published, I’ll have already moved onto to other topics. Moved on more generally. The writing of the essay matters more to me than its reception. I’ve had my say.

**Update: On January 19, 2016, my essay was published at Vitae, Teaching as Liberation. Go check it out!**