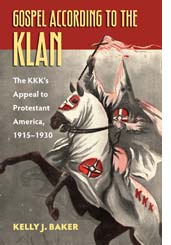

Over at the Bulletin for the Study of Religion blog, there is a “thorough” interview with me on Gospel According to the Klan, methods and pedagogy. There is also a good dose of apocalypticism and zombies minus any discussion of recent spate of news stories about face-eating. Here’s an excerpt:

Over at the Bulletin for the Study of Religion blog, there is a “thorough” interview with me on Gospel According to the Klan, methods and pedagogy. There is also a good dose of apocalypticism and zombies minus any discussion of recent spate of news stories about face-eating. Here’s an excerpt:

How did you get started on researching Gospel According to the Klan?

This project grew out of my personal experiences growing up in the South, as well as a natural outgrowth of my academic work. I grew up in a small town in the Florida panhandle. Back in the 1990s, when I was in high school, there was a Klan rally in a nearby town. What I found most interesting about this was the nervousness that everyone seemed to feel, and display, about it. Not just that there might be violence (as it was also said that the Black Panthers planned a rally simultaneously in this same town), but also the attempt to tamp down the tawdriness of the reputation of the Klan, as it might get attached, or re-attached, to these people and places. “It’s in the past… it’s behind us,” was the basic attitude. While many people wanted to nostalgically hold onto some parts of the Southern past, the Klan represented a part of that past from which they wanted as much distance as possible.

As a scholar of religion, I’ve been intrigued by the ways in which groups like this tend to be understood in my field of study. It is often assumed that religious people we do not like are relatively easy to figure out and are thus not worth a lot of study, whereas people we do like are worth knowing more about. More, we tend to assume that ‘bad people’ equate to ‘bad evidence’ that necessarily invokes skepticism, while ‘good people’ equate to ‘good evidence’ that we can take at face value. I’m interested in studying and understanding not only the “unloved groups” themselves, but also how we tend to think about them, how we reify such groups and how so doing obscures much more than it tells us analytically. So, in writing Gospel According to the Klan, I wanted to produce a study that unsettles academic norms as to what counts as acceptable research subjects. What objects are worth study? What are not? Where do we draw those lines? What’s at stake when we do so, when we categorize things as ‘good data’ or ‘bad data’? Quite often these judgments tell us more about the researchers who made them than about their actual subjects.

Read more at the Bulletin blog. Cross-posted from Religion in American History.