This is my humble attempt to document those scholars who use gender as a category of analysis in American religious history. The first four on my list were the scholars whose work has most deeply influenced my own. The rest of my list includes scholarship I love as well as scholarship that I need to know (and you do too!). My current goal is to list 31 scholars for the 31 days of NWHM. Let’s see if I can do it!

So, the list continues on:

5. Catherine Brekus, the editor of The Religious History of American Women: Reimagining the Past and author of Strangers & Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845, is one of the strongest voices about the inclusion of women in American religious history. Her introductory piece to The Religious History of American Women pulls no punches. She writes:

More than thirty years after the rise of women’s history alongside the feminist movement, it is still difficult to ‘find’ women in many books and articles about American religious history…[M]any seem to assume that women’s stories are peripheral to their research topics, whether Puritan theology or church and state. They do not seem hostile to women’s history as much as they are dismissive of it, treating it as a separate topic that they can safely ignore. Since ‘women’s historians’ are devoted to writing women’s history, those who simply identify themselves as ‘American religious historians’ can focus on topics that seem more important to them (1).

Brekus makes it clear that American religious history needs to attend to gender and her contributors showcase how studying the lives of women change the tenor, strategies and narration of American religious history. I reread her introductory essay, whenever I need a kick in the pants to do good gender analysis as a method to improve my scholarship. Women’s history is not just the purview of women’s historians.

6. Evelyn Higginbotham is the author of Righteous Discontent:The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church: 1880-1920 (1993). While I am not the most familiar with her work, I should be. Harvard University Press describes this ground-breaking and award-winning work:

In her account, we see how the efforts of women enabled the church to build schools, provide food and clothing to the poor, and offer a host of social welfare services. And we observe the challenges of black women to patriarchal theology. Class, race, and gender dynamics continually interact in Higginbotham’s nuanced history. She depicts the cooperation, tension, and negotiation that characterized the relationship between men and women church leaders as well as the interaction of southern black and northern white women’s groups.

Righteous Discontent finally assigns women their rightful place in the story of political and social activism in the black church. It is central to an understanding of African American social and cultural life and a critical chapter in the history of religion in America.

7. Amy Koehlinger, a contributor to The Religious History of American Women, the author of The New Nuns: Racial Justice and Religious Reform in the 1960s (2007), and one of my mentors, helped me wrestle with Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble as well as informed my approach to 1920s Klan femininity and masculinity. Amy’s work on Catholic nuns and their struggles in the Civil Rights movement analyzes race and gender in tandem and demonstrates how nuns negotiated their new roles during the advent of Vatican II. Her new project, titled Rosaries and Rope Burns, explores importance of boxing for Catholic men as well as examines how the sport influenced performances of masculinity. This isn’t first time she’s tackled masculinity. Her essay, “Let Us Live for Those Who Love Us’: Faith, Family, and the Contours of Manhood among the Knights of Columbus in Late Nineteenth-Century Connecticut” in the Journal of Social History, takes to task Mark Carnes’s work on fraternities in the Victorian era for focusing solely on Protestant men’s attempts to move away from domesticity. The Knights of Columbus, on the other hand, imagined their fraternal work as an extension of their family life.

8. Lynn Neal is the author of Romancing God: Evangelical Women and Inspirational Fiction (2006) and a co-conspirator when it comes to all things religious intolerance. Romancing God explores the relationships of evangelical fiction to evangelical romance novels, and Lynn takes seriously the piety and devotional reading of these Christian women. Rather than disparage the romance novel, she explores the complicated relationships evangelical women have with the books that they read and how this genre influenced their practices of Christianity. (I’ve blogged about Lynn and Amy’s work long ago.)

8. Kathleen Sprows Cummings is the associate director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism, author of New Women of the Old Faith: Gender and American Catholicism in the Progressive Era (2009), and contributor to The Religious History of American Women. Kathy also blogs at with outr much beloved crew at Religion in American History. Her work employs case studies of Catholic women to demonstrate how debates over Catholic identity during the Progressive era were also negotiations of gender roles. She has written deftly about the place of women religious in Catholic infrastructure.

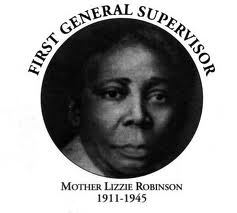

9. Anthea Butler, who I follow at Religion Dispatches, is the author of Women in the Church of God in Christ: Making a Sanctified World (2007). Butler’s work engaged me as soon as she cataloged the fashion of the women of COGIC and discussed the ways in which fashion cleared up the problem of sanctified women’s bodies. Here’s what I said about her book at the Journal of Southern Religion:

Moreover, fashionable dress might present a gender-confused body. For members, “the Spirit could not move into a body that was ‘confused’ about its gender identity,” which meant that women policed the clothing of other women to guarantee one could become sanctified (79). Additionally, dress was the preferred method of controlling men’s sexual behavior. By dressing modestly, COGIC women differentiated themselves from prostitutes and appeared “respectable” (80-81). For Butler, dress is also the signal for changes within the denomination. Restrictions of dress emphasized the importance of self-sanctification, and the embrace of more fashionable attire signaled the engagement of church mothers with the larger world. To become civically engaged, these women had to retire plain dress and be “a smartly dressed, well-coiffed and well versed church mother with a vocabulary steeped in scripture yet attuned to the social realities on earth, rather than heaven” (136). The evolution of the Women’s Department from 1911 to the 1960s could be traced sartorially. Their dress signaled their spiritual concerns, and their clothing shifted from a material artifact representing inner purity to smart clothing that symbolized a concern with the larger world. For Butler, by the 1970s, clothing had been stripped of much of its religious meaning, and well-dressed women were no longer engaged, but submissive to the commands of male leadership.

Her careful attention to the sartorial and the complexity of gender performance for COGIC women makes this one of my beloved examples of Pamela Klassen’s assertion that the history of religion is a history of clothing.

10. Bret Carroll‘s article on the mediumship of John Shoebridge Williams is one my favorite academic articles, which is not a title I pass around lightly. Carroll uses the diaries of Williams to show how the medium faced conflicting norms of masculinity in Spiritualism but also larger 19th century American culture. Williams had a peculiar dilemma, in that he believed he was growing breasts because his daughter, Eliza, possessed him. I recently taught this article in my gender seminar, and my students were a bit flabbergasted. Yet, the complexity of masculinity, femininity and the problem of androgyny appear in this well-written and humorous article about one male medium’s struggle with his gender performance. Feel free to rush to JSTOR for your reading pleasure.

Note: The University of North Carolina press is not influencing my choices with any monetary gains. They just rock when it comes to gender scholarship in American religious history.

[Cross posted at Religion in American History on 3/18]