As mentioned in my post last week, I want to highlight the scholars who take gender and women seriously in American Religious History for National Women’s History Month. Below, I have provided my first four scholars, and these are the folks that I find most pivotal when I think about the power of gender history to inform and change American religious history. As one might tell, I have favorite pieces of scholarship from each, and each has a large body of scholarship to draw from. The ones I highlight are the ones that influence me most deeply as a scholar.

Here are they are:

1. Ann Braude, of course, is at the top of my list. Her works include Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-century America (2001), Sisters and Saints: Women and Religion in America and several edited collections, notably Transforming the Faiths of Our Fathers: The Women Who Changed American Religion. Her essay, “Women’s History is American Religious History” (1997) is required reading. In this piece, she argues that women’s history is central to the narratives of American religions, and that common descriptors like secularization refer to men’s roles and decreasing presence in churches rather than abandonment wholesale of Christianity. For Braude, religious history looks different from the perspective of women, and this needs to be accounted for in our tellings and retellings of American religious history. Again, I wonder how many have taken seriously her call of the gendered nature of our categories of American religious historiography.

2. Pamela Klassen‘s work on religion and maternity is one of my currently most assigned pieces in my gender classes. While I don’t assign the whole of Blessed Events: Religion and Home Birth in America (2001), I do assign her “Sacred Maternities and Post-Biomedical Bodies” from Signs. Klassen’s analysis of home birth tackles one of the most problematic areas for feminist theory, pregnancy. Her article presents the ways in which home birthing women describe their bodies and what is “natural” as well as what is supernatural about birth. Her explorations of what is at stake in the natural clearly shows how pregnancy is socially constructed and biological. Just because we assume biology doesn’t mean it is. Klassen deftly showcases how the biological becomes paramount in the case of pregnancy, but home birthing women graft social and religious meaning on their bodies as well. They might be “postbiomedical bodies” but they are social bodies as well.

3. Marie Griffith‘s work on Women’s Aglow also appears quite frequently in my classes in American religious history and gender. Much like with Klassen, I don’t assign the whole of God’s Daughters:Evangelical Women and the Power of Submission (1997). Instead, my students read “Submissive Wives, Wounded Daughters, and Female Soldiers…” from David Hall’s edited collection, Lived Religion in America. This haunting piece on the power of submission to God in the lives of women often troubles my students. That discomfort allows for good analysis and equally compelling discussion. I am also deeply in love with Born Again Bodies (2004), which emphasizes the importance/significance of bodies and food in American religious history. Griffith’s assertion of the danger of slimness in religious circles to emphasize certain white, female bodies and the corruptedness of differing bodies stayed with me long after I finished this work. The centrality of bodies to theology also made me rethink my own approach to white, male bodies in my own work. Griffith has just been named the director of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion & Politics at Washington University in St. Louis.

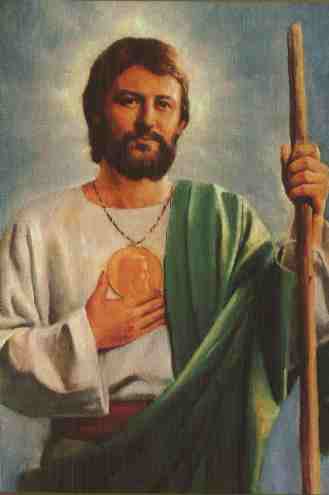

4. Robert Orsi‘s “ ‘He Keeps Me Going’: Women’s Devotion to Saint Jude Thaddeus…” in Religion in American History: A Reader is another constant in my classes. This article is a portion of Thank You, St. Jude: Women’s Devotion to the Patron Saint of Hopeless Causes (1999), which is my favorite book, hands down, by Orsi. Every time I read this article, I find some new layer of complexity from the lovely interweaving of immigrant history, the Catholic Church’s position on women in newsletters, and the material relationships of the women to St. Jude. He writes, “Women…created and imagined themselves, manipulating and altering the available grammar of gender” (349). Moreover, Orsi poignantly notes, “Women believed that they became agents in a new way with Jude’s help” (349). Women believed in agency, but Orsi seems less convinced. This line proved particularly fruitful to my students this semester as they struggled with the question of agency and the desire to see agency even if there is none. Belief in agency startled them and me, and we wondered how St. Jude operates. We pondered what does the attachment to the patron saint of lost causes really mean for women, for Catholicism, and for our class.

Stay tuned for the next parts! Now, cross posted at Religion in American history.