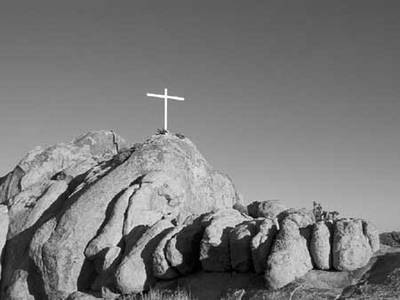

The newest issue of Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief is now available (with a library subscription). For those of unfamiliar with this journal, it is an excellent, interdisciplinary journal that provides cutting edge scholarship on the materiality of religion. Every time the table of contents arrives in my inbox, I stop whatever I am doing to see what the issue holds. The July issue is no different, and it contains a conversation about sacred space in America with Erika Doss, Anthea Butler, Jacob Kinnard, and Edward Linenthal. From outdoor space at the U.S. Air Force Academy for Wiccans and Druids to worship to a disappearing cross in the Mojave to “the shadow of ground zero” to the Enola Gay, ordinary spaces become sacred, contested, desecrated, and defiled.

The newest issue of Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief is now available (with a library subscription). For those of unfamiliar with this journal, it is an excellent, interdisciplinary journal that provides cutting edge scholarship on the materiality of religion. Every time the table of contents arrives in my inbox, I stop whatever I am doing to see what the issue holds. The July issue is no different, and it contains a conversation about sacred space in America with Erika Doss, Anthea Butler, Jacob Kinnard, and Edward Linenthal. From outdoor space at the U.S. Air Force Academy for Wiccans and Druids to worship to a disappearing cross in the Mojave to “the shadow of ground zero” to the Enola Gay, ordinary spaces become sacred, contested, desecrated, and defiled.

Doss argues that public debates are both “sweeping–indicative of widespread interests in claiming public spaces and places as an extension of personal values and beliefs–and presentist–driven by the inconstant and fluctuating aims and concerns of particular publics at particular historical moments” (270). What becomes sacred space and who claims its sacrality emerge as crucial components of public debate. The contributors note how questions of space, and whether it is sacred or not, become markers of deep religious intolerance in contemporary America. Contestations over sacred space become contestations over the place of religion in public life, and certain religions garner more legitimacy, cultural capital.

Butler writes about how a cross in a desert emerges in discourse as both a religious and a secular symbol, and the spa ce it inhabits, thus, becomes significant and ambiguous. Its absence even more so. Kinnard emphasizes that the debate over Park51 becomes an”easy synecdoche” to understanding the place of Islam in the nation (275), and the all of America becomes a “ground zero” with any mosque nation-wide, a violation. Linenthal ponders the ease at which sites of mass murder become sacred to Americans and how space becomes sacred, if it can be defiled. Space can emerge as separate from the ordinary because of the “power of events on the land (279). For Linenthal, the Enola Gay, an object and a space that housed and dropped an atomic bomb, functioned both to sacralize and the desecrate, and it could not be easily managed. This space was wrought, like the other examples in this issue, with questions of legitimacy, illegitimacy, redemption, terror, and narrative authority. Who makes a space sacred and what are the costs? The confrontations over sacred space, then, provide a way to understand the place of religion in public discourse and its material presence.

ce it inhabits, thus, becomes significant and ambiguous. Its absence even more so. Kinnard emphasizes that the debate over Park51 becomes an”easy synecdoche” to understanding the place of Islam in the nation (275), and the all of America becomes a “ground zero” with any mosque nation-wide, a violation. Linenthal ponders the ease at which sites of mass murder become sacred to Americans and how space becomes sacred, if it can be defiled. Space can emerge as separate from the ordinary because of the “power of events on the land (279). For Linenthal, the Enola Gay, an object and a space that housed and dropped an atomic bomb, functioned both to sacralize and the desecrate, and it could not be easily managed. This space was wrought, like the other examples in this issue, with questions of legitimacy, illegitimacy, redemption, terror, and narrative authority. Who makes a space sacred and what are the costs? The confrontations over sacred space, then, provide a way to understand the place of religion in public discourse and its material presence.

[Cross-posted at Religion in American History]