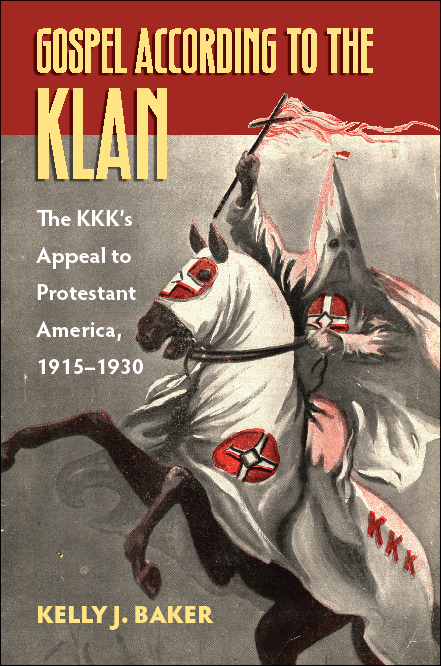

Gospel According to the Klan

Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915-1930. Culture America. University Press of Kansas, 2011.

Gospel According to the Klan employs the Ku Klux Klan as a case study of the intersection of Protestantism, nationalism, whiteness, and gender in the early twentieth century. The Klan, rather than being a fringe movement in narratives of American religious history, proves to be more mainstream, and essential, to narratives of American culture, patriotism, politics and American Christianity. The 1920s Klan was a Protestant movement that couched its religious and racial hatred in Christian virtue and devotion, and that the conflation of Americanism and Protestantism showcases the impact of this particular faith (in a variety of forms) on the development of American culture more largely. To understand the rise and fall of the Klan in American history complicates previous narratives that ignore the centrality of race and Protestant Christianity to the creation of national consciousness. The Klan’s vision of America was not so different from that of its peers, but adding Klansmen and Klanswomen to our narratives implores a darker reading of religious nationalism and American Christianity than we currently enjoy.

To use the Klan as an interpretative lens changes the historical landscape by illuminating trends of intolerance and violence that permeate our culture. The Klan’s narratives provided members with the historical assurance that the Klan, and by extension white Protestants, were to remain the real heirs of American culture

and to maintain a favored position of dominance. Its nationalism shows how Americans embraced the centrality of white Protestant superiority and disdained those who did not fit neatly into this narrative. Ironically, in our continued exclusion of the Klan from our narrative, we remain blind to the nefarious foundations of nationalism in the twenty-first century. Using Klan print culture and presenting Klan members in their own terms illustrates their experiences in the fraternity and the larger world. To see the Klan as citizens rather than villains clarifies a more complex American story.

Praise

A splendid book–a major contribution to a rethinking of twentieth-century American religious history and to the history of American intolerance. Baker’s compelling study places religion, specifically white Protestantism, squarely at the heart of the 1920s Ku Klux Klan in a way that no other author has done.

—Paul Harvey

An original and sobering work. In the present age, when we may no longer pretend that the lines between violent fanaticism and religious fervor are clearly discernible, this book makes a timely and urgent intervention. Hatred may have more to do with religion than we care to acknowledge.

—David Morgan

A brave new book. Baker has exposed something about American cultural history that many of us may not wish to see: namely, that both religion and mainstream society participate in the ugly, even violent, side of American nationalism.

But Baker seems closer to the mark when she says that there’s a dark strain of bigotry and exclusion running through the national experience. Sometimes it seems to weaken. And sometimes it spreads, as anyone who reads today’s papers knows, fed by our fears and our hatreds.

[W]ell-written, persuasively argued book…Her suggestion that the Klan’s intertwining of nationalism and religion makes it part of the lineage of the American Right is particularly provocative, and sure to stimulate some heated discussion. Highly recommended.

—Sean McCloud

This book is an important intervention into current conversations about dark expressions of American religion. With historical rigor and theoretical ambition, Baker weaves together material culture studies, discourse analysis, and political history to show that the Klan be as safely othered as contemporary interpreters might like.